Reading time: 8 minutes

Your story is remarkable for its rapid pace. After all, it started only five years ago …

It all began in 2021, when Robin Simsa presented a business idea as part of his PhD programme in Vienna. The plant-based meat market was starting to develop at that time, but the fish market niche remained unoccupied.

It is such an original idea!

Fish is enormously important; thousands of tonnes are produced every year – but we are all aware of the pitfalls of fish production. Aquaculture farms are overcrowded, and the fish have to be treated with antibiotics to prevent infection. Then there's fishing in the open sea with trawl nets, which churn up the seabed and release vast quantities of CO₂. We were convinced that fish deserve the same compassion as humans and other animals, and that there might be a way to produce fish meat without killing fish.

And then it all happened very quickly ...

In our first year, we launched a smoked salmon product based on pea protein. We also secured a listing in Billa supermarkets after appearing on the Austrian TV show ‘2 Minuten – 2 Millionen’ (‘2 Minutes – 2 Million’). From the outset, our goal was to develop more complex products, such as whole cuts – fillets, to be precise. We had to ask ourselves: what is the best way to produce them?

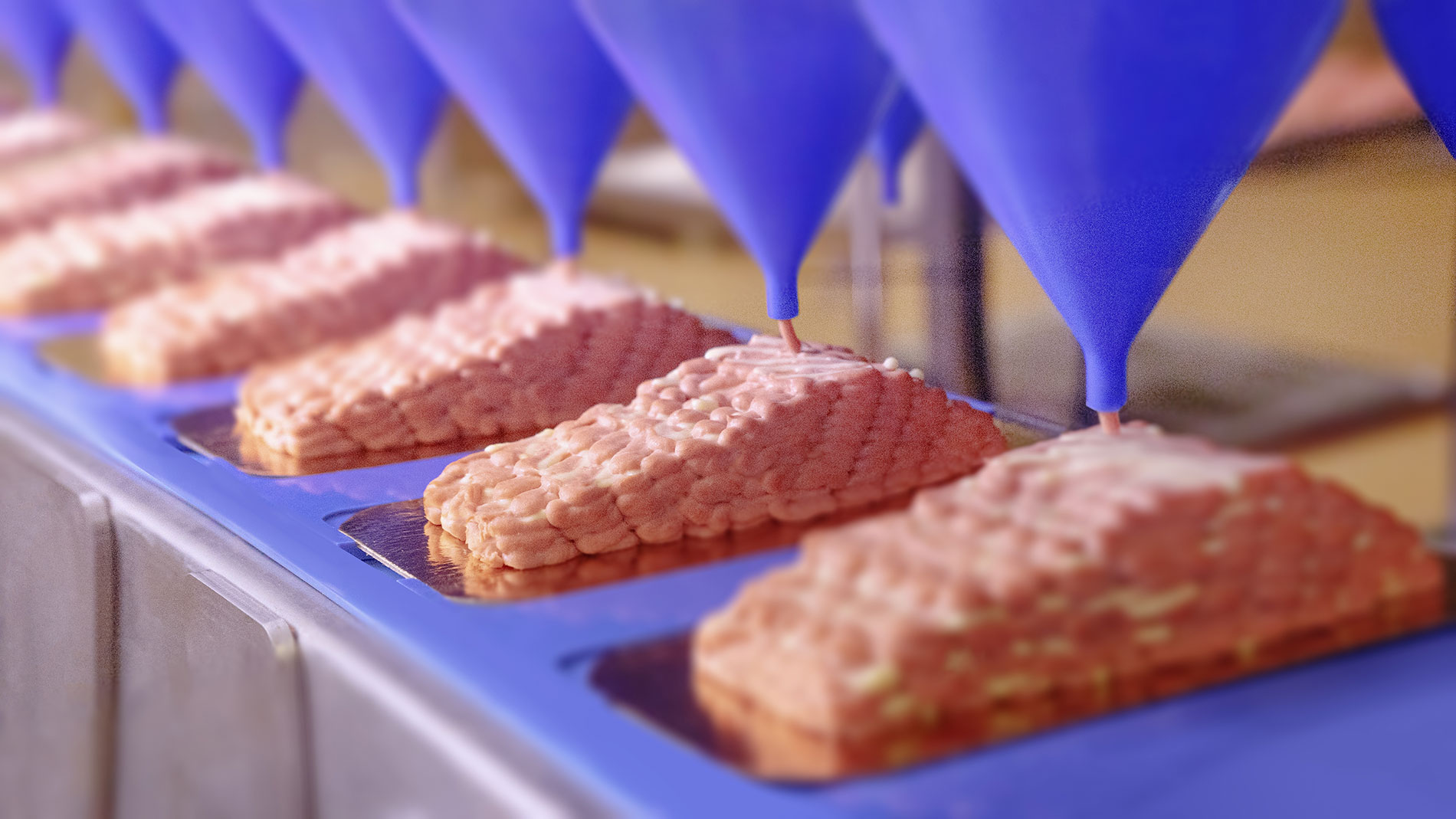

This is when Manuel Lachmeier, our 3D printing expert and third founder, entered the picture. The machines we work with today were only fully built in 2024. We now no longer produce the smoked salmon in our own facilities, but we do use our machines at the ‘Taste Factory’ in Vienna for our fillets. At the moment, our most successful product is the ‘Blanco’ fish fillet.

Your first successful product was smoked salmon. Since then, you have switched from using peas to using mycoproteins derived from mushrooms, which are a much better source of protein.

Our production was very limited at first, with only six or seven kilos a day. Today, we produce seven tonnes a month. We had to start small, however, in order to develop the production process, including hygiene, food regulations and the integration of mycoproteins. Salmon was a good starting point because it is very complex. The recipe for white fish fillets is much simpler.

Quick side question – how do you make food taste ‘fishy’?

We only use plant-based flavours and do so by isolating molecules that naturally have a fishy note. We also use microalgae oil, not only to give the product its fishy taste, but also to incorporate omega-3 fatty acids. Fish only contain omega-3 because they eat algae. By adding the algae to the product, we go straight to the source.

You have always said that you want to extend your product range beyond salmon. How exactly does that work for you; what steps are you taking? Are meat substitutes also an option?

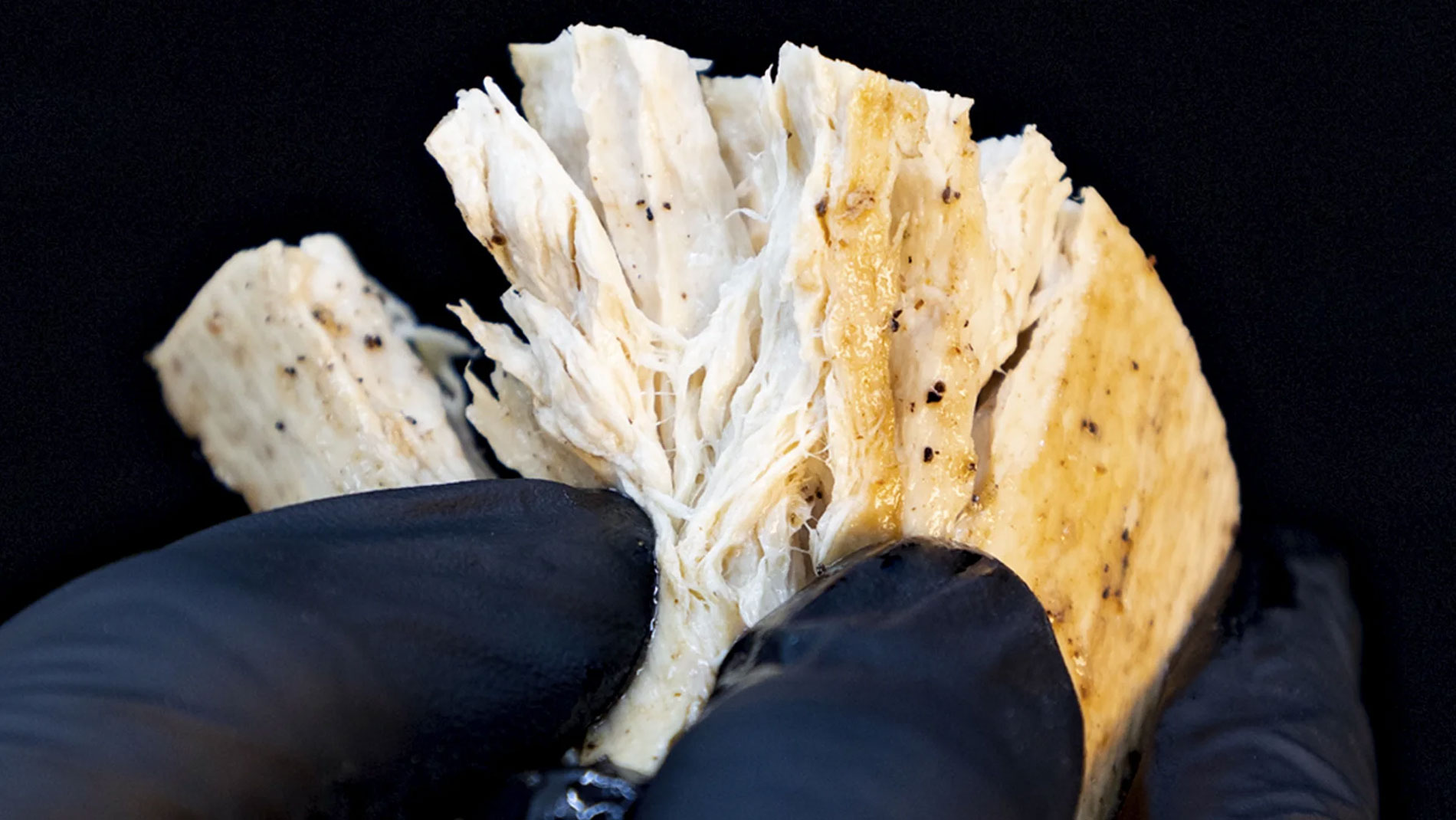

It is a matter of trial and error. We had a squid product — the octopus — which we have now re-released in a new version. After establishing mycoproteins as our base, we thought we could venture beyond fish and launched our mushroom mince, which is chopped or mixed rather than 3D-printed. It is a simple recipe with the same main ingredient. Then we launched Prime-Cut, which is also mushroom-based. We describe it as ‘innovative protein from mushroom fermentation with a hearty umami flavour’ – it is not meant to be an imitation of anything. We wanted to move away from the expectation that our products always have to taste like an ‘original’ of some sort.

Let's talk about technology. How are you using 3D print, exactly?

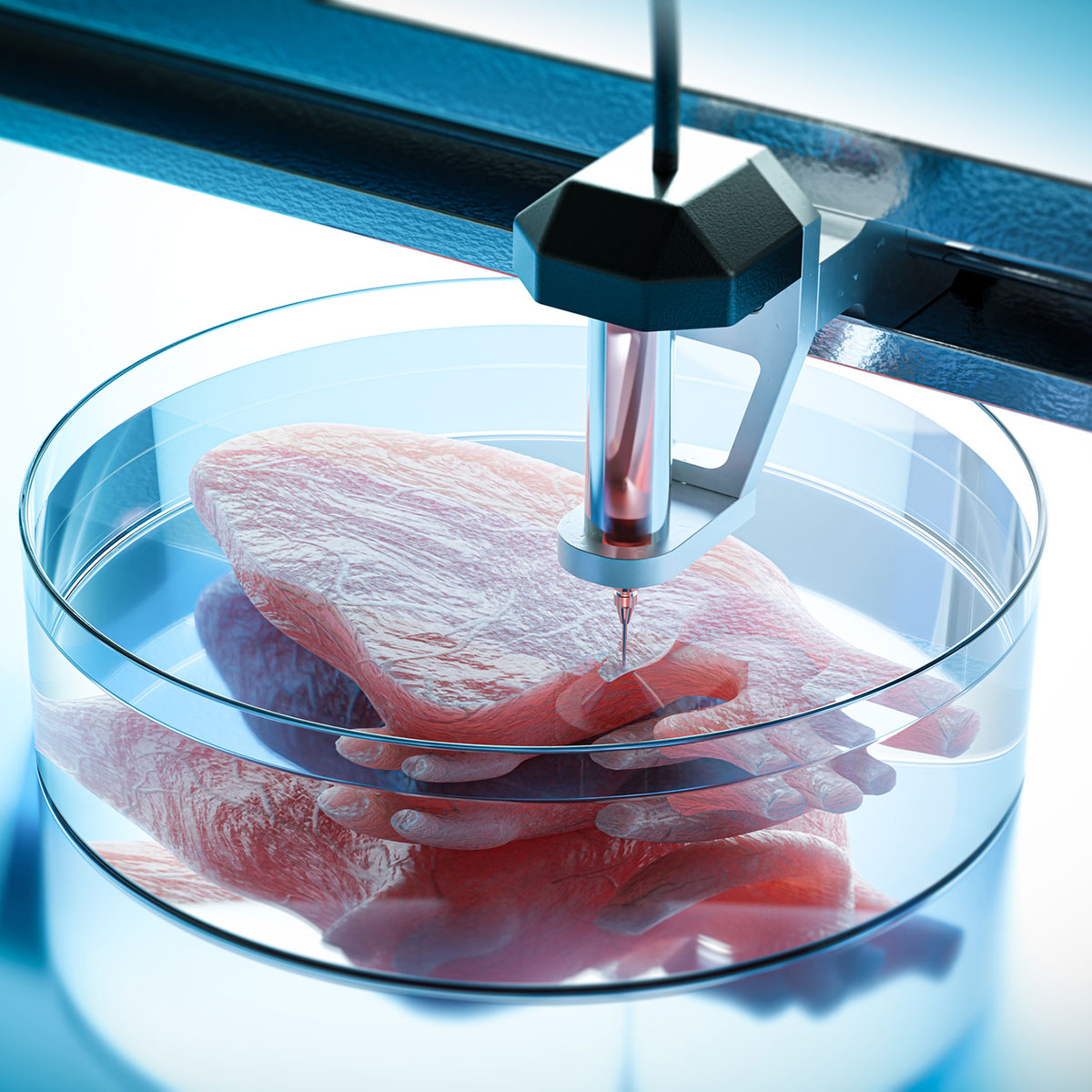

We source the raw materials, including mycoproteins, and mix them according to our recipe. The mixture is then loaded into the material tank of the 3D food printer, and auger screws carry the mass through the system. This way, we were able to develop a continuous process for the very first time; previously, the printer had to be refilled manually after each fillet was produced. In our current design, the material is automatically fed into the nozzles. Two nozzles then simultaneously print the protein and fat masses for each fillet, creating the typical layering effect and a consistent fibre structure.

So, 3D printing is used to create the texture of the food …

We achieve a very different texture by printing protein and fat simultaneously instead of using compression methods. Many plant-based products rely on high-moisture extrusion, in which proteins are shaped at high temperatures and under intense pressure – take chicken substitute products like the chicken chunks commonly found in supermarkets, for example. Our process is much gentler, preserves more nutrients and delivers a loose, fibrous structure.

Currently, your setup enables you to manage the entire production chain in-house – from sourcing and manufacturing to distribution. You control every step of the process.

I often say that we are doing too much, actually.

Alternatively, you could focus on offering your technology rather than your products.

For now, we still have to run our business in parallel: without products, there would be no technology, and without technology, there would be no products. But I believe that in the long term, going down the technology route will be easier for us. We are also working on new recipes, employ trained food technologists, conduct research in mechanical engineering and develop electronics and software. Then there is production itself, followed by marketing, sales and logistics. Our products are now available at Rewe and Edeka in Germany, too. It is quite remarkable how much we have been able to do in such a short time.

How important is the price?

Achieving price parity with meat products is our main goal. The plant-based market is already well on its way, at least for smaller quantities. Compared to cultivated meat, our process has one key advantage: we only use plants and oils. There is no need for expensive cell cultivation stages. We mix pre-approved raw materials, which we blend according to our recipes – a process that is far simpler than cultivating meat, which is why our products are already available in supermarkets and cleared for sale. Both approaches tackle the same problem, but in completely different ways.

How much flexibility do you have when it comes to adjusting prices?

We feel the pressure from all sides. As a small business, we have little bargaining power with our suppliers, and we have just as little with our customers — in our case, the supermarkets. They wield so much market power that they can exert considerable influence, push quite hard. Operating in this environment can be a real challenge.

What is the current mood in the market?

People say we had a pretty good upswing, but things are now slowing down due to the economic crisis. There is uncertainty among investors. Beyond Meat had a successful IPO in May 2019 and achieved a market capitalisation of almost four billion dollars. Today, share prices are down to one per cent of that amount, which is challenging for the entire industry. We are also seeing the impact of the meat industry’s lobbying efforts on consumer behaviour.

In what way?

Misleading information is on the rise – for instance, claims that plant-based products are ‘highly processed’ and far from organic. We challenge this belief by using 100 per cent natural ingredients and our mycoproteins, which offer higher bioavailability and more protein per 100 calories than beef. The term ‘highly processed’ is often used to refer to products with high sugar or saturated fat contents. Our products, by contrast, are high in protein and fibre and low in sugar. And yet it is difficult for small companies to push back against such campaigns. While we are well-received within the vegan community, our main target audience should be flexitarians, who already make up over 40 per cent of the population in Germany. This is why we need to keep trying new things.

There is an ongoing debate about banning terms such as ‘meat’ and ‘sausage’ for alternative proteins. What are your thoughts on this? How important are these labels?

There is so much talk about responsible, informed consumers, and yet we don't trust them to read labels in the supermarket to choose the right items? In our industry, we have heard plenty of criticism of our products – but the idea that anyone would buy our goods by mistake is unheard of. For now, labels based on comparisons to meat products are important, because they serve as a kind of user guide for consumers.

Will people ever move away from these old labels?

It is unclear to me why only animals should be referred to as ‘meat’, even though resolving the issue may take some time. People have imagination and are capable of abstract thinking: there are no babies in baby food, nor are there bears in gummy bears.

In any case, it is unlikely that such a ban will be introduced anytime soon, as it would first have to be implemented into national law, and there would certainly be plenty of debate along the way.

At a glance: Meat alternatives and their differences

Even within professional circles, the terminology gets muddled every now and then. How are different types of meat alternatives produced, and what are their respective advantages?

- Cultured meat

Cultured meat, also known as lab-grown or cell-based meat, is manufactured by cultivating animal cells in a controlled environment. Extracted muscle cells form tissue that is similar to conventional meat at a cellular level. While offering the taste, texture and nutritional value of animal meat, it does not require livestock farming or slaughter and can significantly reduce environmental impacts such as land use, water consumption and emissions.

- Fermented meat substitute

Fermented meat substitutes are produced using microorganisms, such as yeast or fungi, to create proteins. Modern production processes are employed to create protein masses (biomass fermentation) or ingredients (precision fermentation) for alternative protein products, such as meat substitutes. As a tried and tested method, fermentation is now increasingly used in the production of meat and milk substitutes, since microbes can yield large quantities of protein in a short amount of time. These proteins are then harvested and processed into meat-like products. The process is resource-efficient, scalable and can play a significant role in delivering alternative sources of protein.

- Plant-based meat

Plant-based meat is perhaps the best-known of the three alternatives and already widely available in supermarkets. It is made from proteins derived from plants such as soy, peas or wheat, and processed to imitate the taste, texture and appearance of real meat.

Important differences2

Cultured meat is produced directly from animal cells, fermented meat substitutes are derived from microorganisms such as yeast, fungi, or bacteria, and plant-based meat is made from plants.

Production

Cultured meat replicates the biological process of muscle growth, fermented meat substitutes are based on microbial fermentation, and plant-based meat uses plant ingredients that are processed to resemble meat.

3D printing

3D printing is used in cultured meat, fermented meat substitutes, and plant-based meat alternatives, albeit in different ways. In the cultivation of meat, it is used to create protein-based, water-soluble scaffolds. In plant-based and fermented products, however, 3D printing provides structure and texture, creating the typical layering effect that replicates fibre content and nutritional values.

Environmental impact

In terms of CO₂ emissions, water consumption and land use, all three alternatives are more environmentally friendly than conventional meat. For now, plant-based products are the most scalable and resource-efficient option. Although cultured meat has great potential, it is not yet economically viable on a large scale, as it requires significantly more capital and research than plant-based alternatives. What is more, regulatory approval processes for new food items can often take a long time.

Consumer availability

Plant-based meat is now widely available, whereas fermented meat substitutes are only produced in small quantities and – depending on the respective ingredients – approved for specific companies in select markets, e.g. in parts of the United States, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand and Israel.

Each of these meat alternatives has the potential to transform the food industry by enabling diversification of protein sources.

Sources

1 YouTube (2024): Welcome to the TASTE FACTORY, the world's largest 3D food printing facility. Video available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iT9Gnj2GnLA [Accessed 23 September 2025].

2 World Animal Protection (2023): What’s the Difference Between Plant-Based Meat, Cultivated Meat, and Fermentation-Based Meat? Available online at: https://www.worldanimalprotection.us/latest/blogs/whats-the-difference-between-plant-based-meat-cultivated-meat-and-fermented-meat/ [Accessed: 23 September 2025].

Pictures: dropStock