Reading time: 5 minutes

Salt, millions of years old, but with an expiry date. Vegetables that are still being ploughed into the ground because market prices have plummeted. And the Christmas cake that suddenly ‘expired’ shortly after Christmas. These are just a few examples that tell the same story: food doesn't simply go off, it is made to go off. Standards, markets and expectations turn fresh produce into disposable goods.

When freshness becomes a reason to dispose of food – obsolescence in the food industry

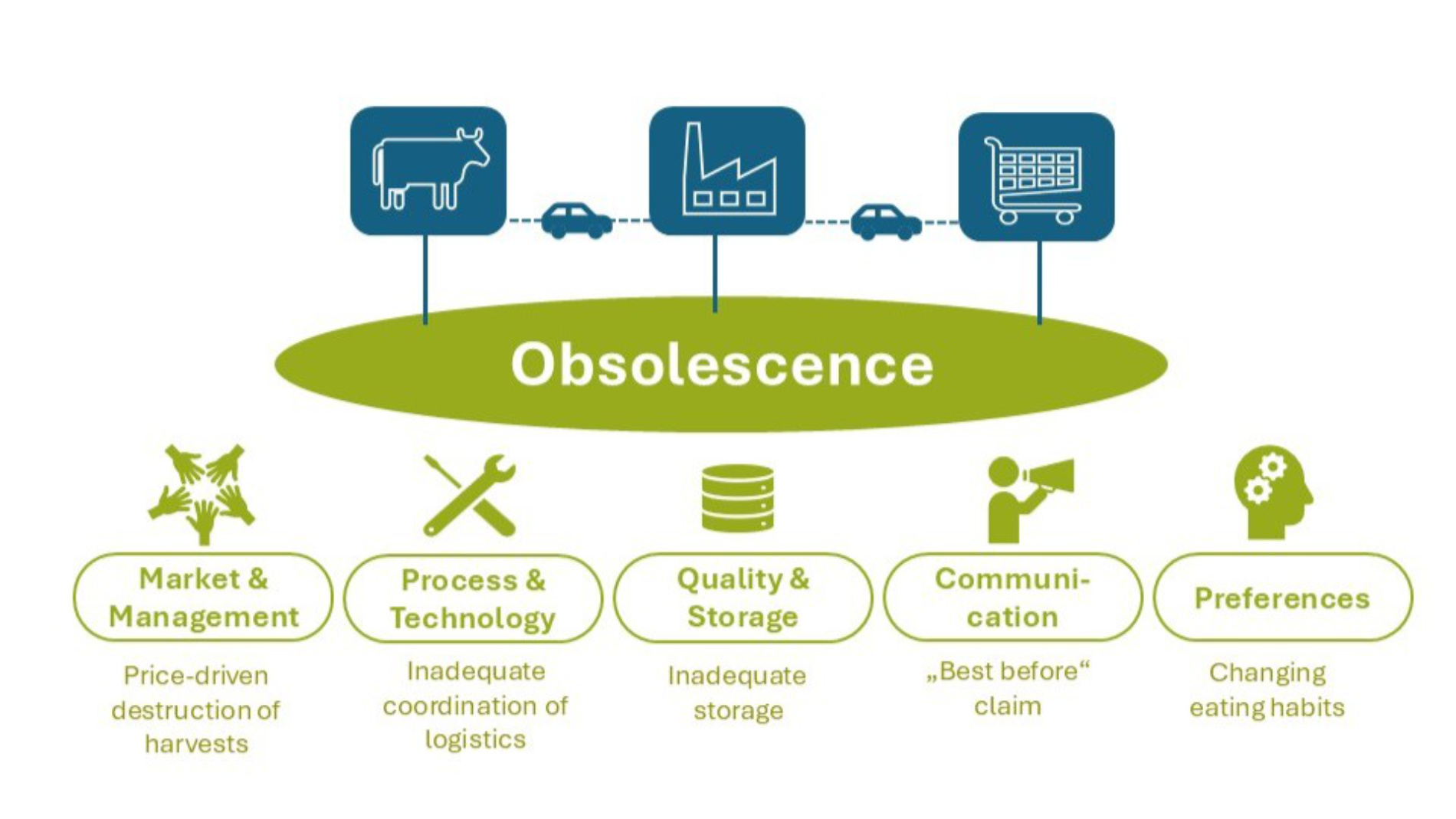

Food does not simply go off – it is forced into obsolescence. This is the conclusion reached by 19 practitioners and scientists surveyed as part of a study conducted by the University of Hohenheim. Numerous mechanisms can be seen along the entire value chain – from the production to the consumption stages – which shorten the shelf life of food, either wilfully or through negligence.

A primary example of this is the expiration date that, according to experts, "... is arbitrarily determined by manufacturers whereby misinterpretations by consumers make it possible to use this information specifically to increase quantities and profits."

Originally used in engineering, ‘obsolescence’ describes the process of premature ageing or a planned lifespan reduction. A legendary example of this is the agreement between leading light-bulb manufacturers in the 1920s, known as the Phoebus cartel, which artificially limited the lifespan of incandescent lamps. Applied to food, the term offers a new perspective: away from the sole responsibility of consumers, towards a systemic view taking account of all actors along the food chain.

The Hohenheim study considers this approach to be a ‘corrective measure’ because many causes of food waste occur before the food reaches the refrigerator – in production standards, distribution logistics and market mechanisms. The corrective measure of consumer responsibility also acts as a correction in the way solutions are approached, resulting in a broader range of measures. Experts agree that legislators have a key role to play by initiating structural changes via flanking regulations and refining the best-before date. The solution can only be achieved if all concerned work together.

Around 80 kg of food waste per person

The amount of food wasted is staggering. In 2022, around 10.8 million tonnes of food waste was generated in Germany – enough to feed a city such as Berlin for a year. According to the German Federal Environment Agency, around 58 percent (approximately 6.3 million tonnes) of this waste comes from private households and 15 percent (approximately 1.6 million tonnes) from food processing; the remaining amounts come from retail, out-of-home catering and agriculture. On average, everyone in Germany throws away around 80 kilograms of food per year, much of which could be avoided.

Animal-based food waste has a particularly significant impact on the climate, as shown by calculations published by the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research (IFEU)1. One kilogram of milk generates an average of around 980 grams of CO₂, while beef accounts for up to 14,100 grams of CO₂ per kilogram. And although meat waste appears to be small in terms of quantity – around 2 percent for beef and 6 percent for pork – it accounts for almost half of all greenhouse gas emissions produced in the EU by discarded food.

Systematic food waste reduction

Following approval by the European Parliament in September 20252, the EU has now adopted binding reduction targets for food waste for the first time. By 2030, member states are to reduce waste volumes in processing and manufacturing by 10 percent and in retail, catering and households by 30 percent compared to the average of 2021 to 2023. These targets mark a turning point by obliging all actors along the food chain to implement structural changes rather than focusing solely on consumption. Member states must now incorporate this directive into national law.

Establishing a value appreciation chain

Technological and organisational solutions are already emerging to bring about a measurable reduction in food waste. In agriculture, sensor technology, drone technology and digital harvest forecasts facilitate more precise planning and lower losses. In processing and logistics, AI-powered demand planning, smart packaging and real-time monitoring ensure less waste and more stable cold chains. In retail, dynamic pricing algorithms and digital distribution models for surplus goods help use resources more efficiently. And in catering and private households, digital apps and educational initiatives promote a more conscious approach to food. Furthermore, the Centre of Excellence for Food Waste and Food Loss Prevention (KLAV) was established in 2025 as a national platform for waste prevention, offering information programmes, networking structures and monitoring tools for all stakeholders along the chain.

Summarising, an expert from the Hohenheim study says, “Genuine sustainability can only be achieved when all links in the chain understand that value creation cannot work without value appreciation." In this way, the traditional value chain is transformed into a value appreciation chain – a shared approach that avoids waste and conserves resources.

Further information and sources

Obsolescence – a subject that also applies to food

A study by the University of Hohenheim on food waste and losses from an expert point of view. The starting point for the study is the absence of scientific analysis of the correlation between food waste and planned obsolescence.

Learn more (in German language)New EU regulations on reducing food waste

With the updated legislation passed on 9 September 2025, the European Parliament has set binding targets for the reduction of food waste, which must be met at a national level by 31 December 2030.

Learn moreCentre of Excellence for Food Waste and Food Loss Prevention (KLAV)

Established in 2025, this new centre of expertise supports an interdisciplinary exchange of information with the business community and is part of the national strategy to reduce food waste in Germany.

Learn moreNational strategy for the reduction of food waste

Since 2019, the ‘National Strategy’ has provided the framework for jointly defining measures to prevent food waste and achieve a change in social attitudes.

Learn more (in German language)Food waste glossary

Food

European Regulation (EC) No. 178/2002 defines what is meant by food. According to this, food is any substance or product that is intended to be, or can reasonably be expected to be, ingested by humans in a processed, partially processed or unprocessed state. Feed, plants before harvest, animals before slaughter and medicinal products, among other things, are not considered to be foodstuffs.

Waste

Waste is created when the owner of an item no longer wants or is unable to use it, in other words, when they want to dispose of it, perhaps because their tastes, needs or requirements have changed. The German Closed Substance Cycle Waste Management Act (KrWG) defines the term ‘waste’ narrowly and distinguishes between a subjective desire to dispose of something and objective reasons for doing so. Whenever materials or products are returned to the economic cycle because there is demand, a market or alternative uses for them – for example, when edible food is donated to charitable organisations or used for bio fermentation – the term 'waste' ceases to apply in the legal sense.

Food waste

According to the German Closed-Loop Waste Management Act, food waste includes all food that becomes waste along the supply chain, from production, via processing and trade, to consumption. This includes both avoidable losses, i.e., food that is suitable for consumption or further processing but is disposed of, and unavoidable leftovers, such as peelings or bones. From a global perspective, the scale of the problem is extremely serious: according to estimates by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), around 1.05 billion tonnes of food were discarded worldwide in 2022, a volume equivalent to the total production of foodstuffs from January to May.

Food losses

Food losses usually occur in the early stages of the value chain, i.e., before food reaches the retail or consumption stages. These losses concern both edible products and their inedible components. The main causes include harvest and production losses, spoilage in the field, damage during storage, transport or processing, for example, due to unsuitable harvesting techniques, transport damage or inadequate refrigeration. While food losses occur mainly in agriculture and processing, food waste occurs predominantly in retail, catering and among consumers.

Food obsolescence

Food that spoils prematurely or is thrown away even though it is still edible can be seen as cases of obsolescence. The term originally comes from the engineering field. However, a study by the University of Hohenheim shows that this principle can also be applied to the food sector: market mechanisms, ideals of freshness and economic incentives often artificially shorten the useful life of products. The findings to date are primarily qualitative and anecdotal.