Reading time: 6 minutes

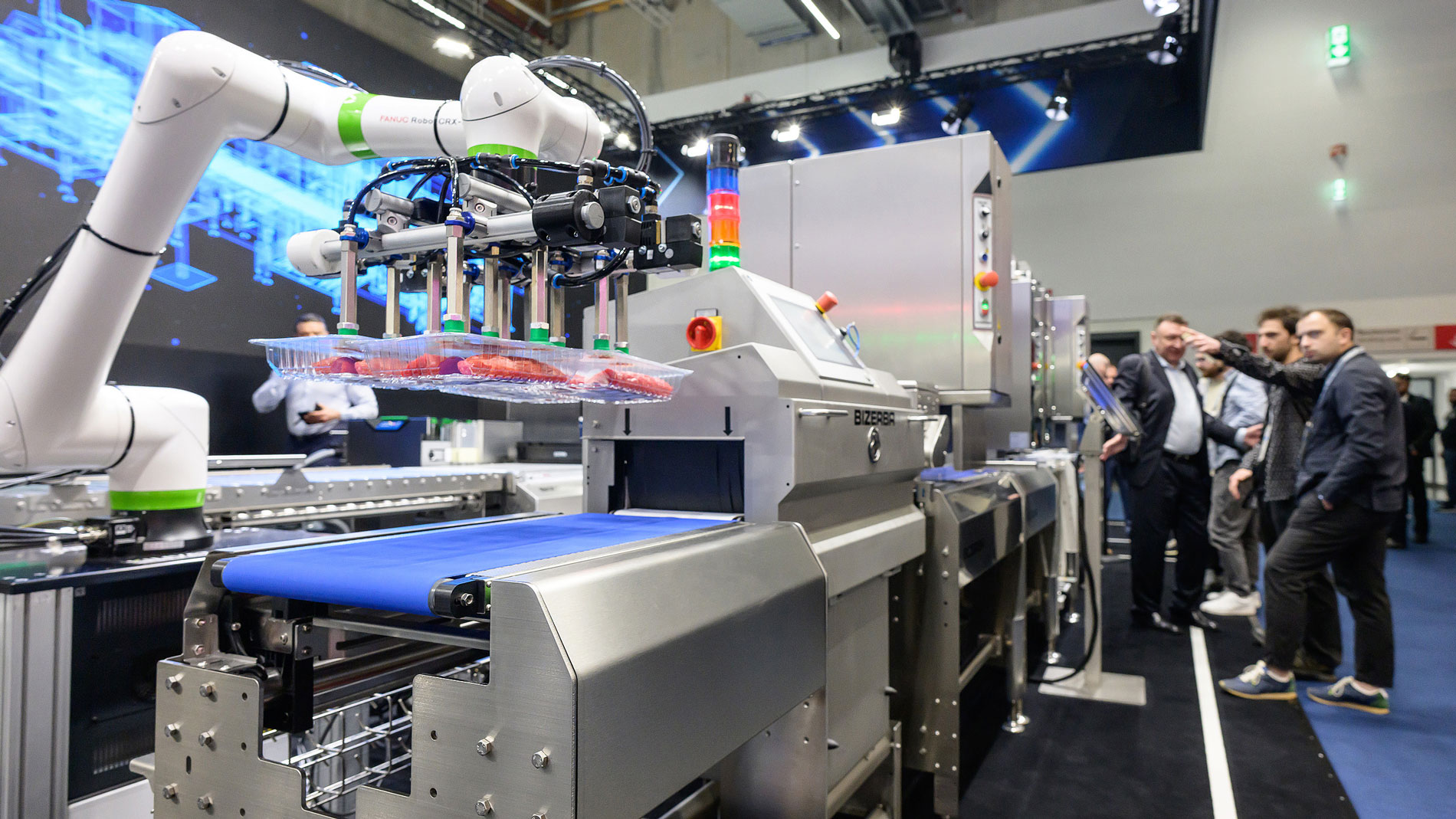

Sausage and meat factories with cleavers and saws – these are a thing of the past. Can anyone still picture them? Production stages today are a whole different story: high-tech laboratories where meat products are cut, shaped, analysed, and packaged with the utmost precision and hygiene. Sensors beep, robot arms move about, cameras monitor every step, and displays everywhere show the data in real time.

Thanks to software and AI, machines can now 'think' for themselves in many ways, taking work off people's hands while also changing their role in the process. Those who used to operate the machines now interact with them differently. They respond to visual or acoustic signals and approve production steps via an intuitive display. Meanwhile, engineers can access real-time data on the same screen and check the networking of the machines, right through to the supply chain.

The terms 'Industry 4.0' and 'Internet of Things' sound almost old-fashioned today, and have long become a reality in meat production. It is becoming increasingly clear just how much potential this new collaboration between humans and machines has.

German meat processing plants – increasingly smarter, increasingly intelligent

German companies are at the top of the league when it comes to innovation in automation and digitalisation. The IFFA Factory Show presented modern technologies that simplify and automate processes along the entire meat processing chain. Of particular note is the interaction of AI with familiar production steps. At CSB in Geilenkirchen, for instance, the expertise of master butchers has been transferred to AI in the form of the ‘CSB Image Meater’ and the ‘CSB Eyedentifier’. These use visual analysis to identify pieces of meat as soon as they arrive, tagging them. They also control cutting, production, and packaging processes and ultimately determine the commercial grade and value of the meat.

Pintro has fully automated the production of sausage rolls, reducing production time by half through the use of robots that position the sausages before rolling them up, based on the pick-and-coil principle.

Jasa packaging lines can switch between packaging modes in a fully automatic way in five minutes (or 15 minutes manually). They can also label products with the correct text in the right place using the integrated printer and respond independently to changes in the recipe.

Sesotec's X-ray and metal detection systems can detect even the smallest contaminants, including glass, copper, stainless steel, rubber, bone, and PVC, on eight lines simultaneously. These processes have been broken down for the user interface so that they can be monitored by untrained personnel.

Intuitive operation is also a top priority at Seydelmann in Stuttgart, where the AE 103/3 automatic meat grinder is so easy to control that even untrained staff can operate the cutting attachments. The benefits of intuitive control panels are a particularly good fit in the meat products manufacturing industry.

Intuitive human-machine interfaces (HMIs) – much more than just control panels

The effectiveness of these processes, which are often carried out ‘as if by magic’, depends heavily on the HMIs that mediate between humans and machines. Designing these interfaces to be intuitive, i.e. making them easy to use without the need for training or the existence of language barriers, opens up new opportunities for companies. They can employ more unskilled workers while simultaneously freeing up skilled workers to focus on more complex tasks. ‘Unskilled labour’ has become a buzzword for this.

“I see a lot of potential in offering machines that work in any language and culture, for local as well as export markets. Pictograms and colour systems on the panels overcome language barriers and achieve more than words could.” As a consultant for the Fraunhofer Institute, Raphael Hägle spends much of his time visiting German companies. Together with a team of designers and programmers, he provides companies with bespoke HMI solutions. He talks about a project in which a conversion process was transferred from skilled workers to operators, resulting in significant time savings.

Despite all the technisation involved, Hägle takes a ‘human-centred approach’, starting with the experience of specific users to further develop operating languages. “Machines are developed with a function-oriented logic and should also be operated in this way,” he tells Foodtech Now! in an interview, addressing a common misconception. “In practice, however, they are often used differently. We take these different perspectives into account. It is not the functionality of the machine that should be the starting point for any machine operation, but the tasks at hand and how the user approaches them.” A detailed interview with Raphael Hägle from the Fraunhofer Institute can be found here.

84 per cent of German machinery is exported. What happens then?

However, walking through German manufacturing halls is not enough to grasp the impact and potential of technology. “Eighty-four percent of the machines manufactured in Germany are exported to regions and countries with very different conditions, such as the Middle East, Mexico, Indonesia, and Nigeria,” says Beatrix Fraese from the Food Processing and Packaging Machinery Association within the VDMA, providing a broader perspective. “In the food sector, many countries are rich in raw materials and can increase their added value through processing and packaging technology. It makes a difference whether raw cocoa or pre-processed cocoa mass is produced, for example, also for the machine operator.” A detailed interview with Beatrix Fraese from the VDMA can be found here.

Automation cannot be forced upon people. “There are many markets where every euro counts, so full automation is not possible,” says Hägle. In Germany, the Fraunhofer Institute is helping small and medium-sized enterprises that would otherwise be put off by the costs associated with approaching topics such as ‘usability competence’ – because this can have an impact even in the short term. “We always have to ensure that machines with new ‘extras’ don’t become too expensive and that the advantages translate into real efficiency gains,” adds Hägle.

Fraese, too, differentiates: "It depends on the maturity of the industries. Some food industries still rely heavily on manual labour for processing and packaging. There are wage structures where it makes perfect sense to employ lots of people. It is only when wages are high that automation processes begin to make sense economically.”

Desert storm, 80 per cent humidity – and new machines

Change of scene: Lagos, Nigeria. Humidity: 80 per cent. From November to March, the Harmattan wind blows desert dust from the Sahara into the cities. Sand being sand, it gets everywhere, and humidity does her part – not ideal conditions for German machinery.

Eben van Tonder is passionate about meat, machinery and the African continent. He advises companies in the food sector on setting up production facilities here. “The machine wears out just standing there,” he tells Foodtech Now! in an interview. “The IP 65 protective cover that comes with the machine is not enough,” he adds. He would always recommend ordering five small machines instead of one large one, as one is always broken. “This makes it easier to compensate.”

On the one hand, Van Tonder is facing the challenge of showing workers how to operate machinery without specific training. Conversely, he criticises manufacturers who, despite the significant growth of the African meat market, do not demonstrate good understanding of local conditions.

Intuitive operation does not play a role here yet either. “What is intuitive?” asks van Tonder. “The way mechanical machines are used in Africa is often different from how they are used in Europe. If you ask a worker about their method, they will say, ‘Because that’s how I do it.’ And sometimes, workers have the attitude that problems will just resolve themselves over time.” A detailed interview with Eben van Tonder can be found here.

Not only the machines are top exports – the training system is too

Like the machines themselves, Germany’s unique apprenticeship system has the potential to become a valuable export. Structured vocational training programmes like those in Germany are not common in the USA. This is why some European machine manufacturers setting up factories there see training their own employees in their academies as the only way to find qualified specialists.

Fraese does not view intuitive machine usability as an educational tool per se, but rather as an opportunity for less qualified individuals to gain entry to companies and learn gradually. “People are presented with tools that they can use effectively, as many displays now resemble smartphones, with which they are familiar,” he explains.

So, what kind of machines would be best suited to Africa? Van Tonder answers this question easily: “African customers don’t want complex programmable logic controllers; they want robust machines with direct drives that are easy to repair, maintain, assemble, and clean. They want machines that are as simple as possible, with affordable spare parts that are readily available. Only machines that tick these boxes are successful in Africa.”

Hägle, working at the Fraunhofer Institute far from Lagos, also recognises the value of simpler technology: “Yes, designing machines with little automation can be exciting, also for markets where simple and robust solutions are crucial.” This doesn't mean that the operation can't be simplified: “Even for a less automated machine, I can build an operating system that guides the user through the task with text, images, and animations. And if something can only be changed with a spanner, for example, the machine will display this, too.”