Reading time: 8 minutes

Looking at the circular economy can make you dizzy. It is so many things at once. First off, it's a trendy term that hardly any discussion in the food industry can do without these days, nevermind the fact that there is little agreement about what the term actually means in today's food production industry with its task division. At the same time, it is an “old hat”, as farms have never operated in anything other than an ecological cycle.

The term circular economy evokes both the past and the future. It refers to the historical archetype of the farm, where production, fertilisation, and feeding form a closed system – and at the same time, it stands for a vision of the future that is about models, principles of climate and resource protection, as well as the implementation of resource efficiency demanded by today's economic market conditions. In the biological cycle, the waste of one is the food of another.

Although regulated by law in Germany and declared a guiding principle in Europe, the call for a circular economy is increasingly being associated with the ‘green’ movement, which tends to favour vegetarian or vegan diets. However, many experts are convinced that a circular economy without livestock would fall short of its potential.

“The organic economy shows how it’s done,” says Beate Gebhardt, an economist and expert on sustainability excellence in the German food industry, “animals are fed on production waste and plant residues from the field, and the manure is returned to the production cycle.”

Circular economy links the past with the future

There is no doubt that ruminant animals can produce milk and meat from biomass that is inedible for humans – meaning they do not compete with humans for food. “What would happen to all the grassland without livestock?” asks Beate Gebhardt, “We can’t grow lettuce on it, the soil conditions wouldn’t allow it.” Economist Gebhardt is a charming realist who always keeps her eye trained firmly on the big picture.

The most successful practices in today’s circular economy are rooted in traditional methods. Utilising as much of the animal as possible, including the by-products, has been taken for granted since the invention of sausage and does not need to be reinvented from scratch. And also fermentation, which is used in the circular economy to utilise biowaste, is a seasoned, natural process that is now being further developed with biotechnology to reach entirely new dimensions.

A host of approaches to combat wastage

Gustav Ehlert GmbH & Co. KG, based in Verl, East Westphalia, has been supporting its customers as a specialist wholesaler for food production supplies and consumables since 1924. “When we were founded more than 100 years ago, we sold natural casings, consumables for butchers in Gütersloh and the surrounding area. These casings are a by-product of pig farming,” explains Gustav Ehlert, a cheerful man who runs the company in the fourth generation and nowadays advises his customers on recycling management – for example, how to bring by-products to market in a sensible way.

Ehlert’s credo: “What did we keep pigs for? To utilise waste, to generate energy and protein. And if you want to put something tasty on the table. And so, the cycle has to be kept going.” In principle, it is already “from field to fork”, says Ehlert. “Nothing can be contaminated with toxins. And what is left over goes back to the field. Or to the biogas plant.”

However, it is not just production that matters, but also the way in which the goods reach the customer, and the packaging it comes in. “One positive example is the development of our vacuum packaging,” says Ehlert, referring to the company’s own products. “There is a lot to be said for saving primary raw materials. Vacuum bags used to be designed with a thickness of 90 microns, but today meat products are produced so well, cleanly, and without sharp bones that a 65 micron film is more than enough. That's a huge potential saving when you consider the quantities we’re talking about.”

To help with another important goal of circular economies –the reduction of wastage during production– disposable clothing plays a key role. “If food is not produced hygienically,” explains Ehlert, “it spoils more quickly and there are higher losses.”

Today, the food circular economy is a combination of different approaches leading to different models and dimensions of economic activity. They range from highly specialised side-stream recyclers to exemplary large-scale beacon operations, from rethinking traditional dairies to spectacularly successful “mushroom pioneers” in the international multi-million dollar fermentation business. There are also a growing number of initiatives to combat food waste, such as Lebensmittelretter (EN: “food rescuers”): from brewing beer using stale bread to the fast-growing scene of “saviour brands”, these groups appeal to the growing group of consumers who value traceable sustainability in their food purchases.

Some examples of successful circular economies

Crowd-Butching

In ‘crowd-butching’, meat is not produced unnecessarily in advance and possibly thrown away in the end – instead, the use of animals is managed communally via shared websites such as meinbiorind.de (Saxony-Anhalt), crowdbutching.com,(a limited company in Bavaria), or besserfleisch.de (based in Hamburg), which works with twelve organic farms in northern Germany. “We are a digital village,” says founder May-Britt Wilkens. “People used to share an animal in the village, now they do it online.” Parts of Galloway cattle from an organic farm in Brandenburg are offered to an online community called “Das gute Fleisch” (EN: “the good meat”). “We definitely don't want an animal to be sent to the slaughterhouse just for a few parts,” says managing director Torsten Siebert, “hopefully consumers will rethink their behaviour.”

„Nose to tail“

Natural casings, the use of bones as flavour carriers for broths and stocks, and the complete use of raw meat in new forms are trends or innovative sidelines in meat companies that can be summarised as “nose to tail”. The colloid mill replaces the traditional cutter in the production of sausage meat from offal, and is also suitable for the production of meat substitutes from tofu or seitan, or soy meat or soy protein meat. Many of these products are also aimed at top restaurants, such as Michelin-starred chef Thomas Imbusch in Hamburg, whose “100/200” in Hamburg harbour is completely ‘nose to tail’. The German premium product veal is also the subject of various initiatives to limit waste and reduce emissions in the supply chain, as well as to guarantee transparency of origin and prove this with certificates of “Kalbfleischkontrolle (EN: “veal inspection”).

Turning whey into heat

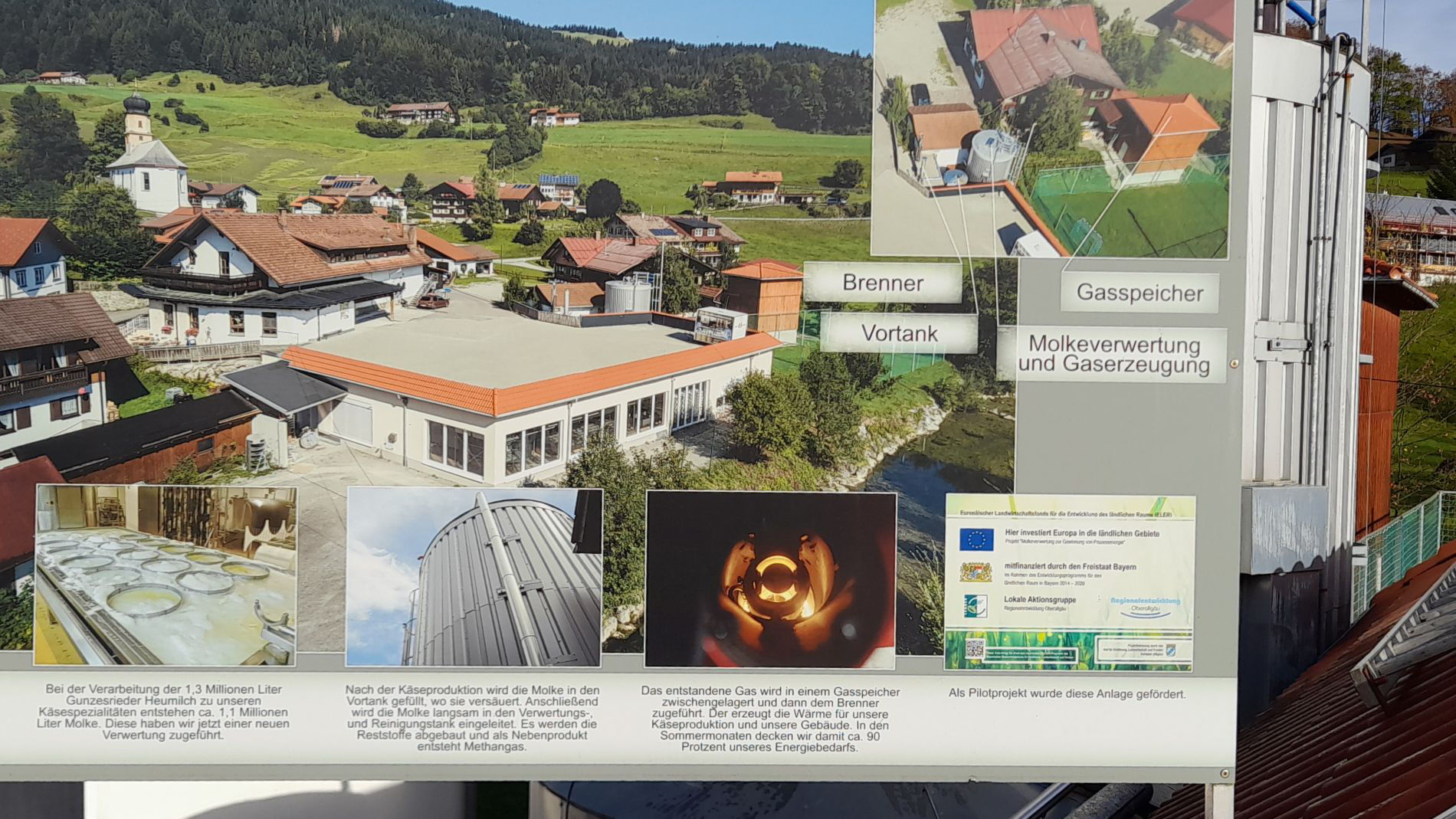

The cooperative alpine dairy in Gunzesried was founded in 1892 and is the oldest continuously producing alpine dairy in Bavaria – with one of the most modern upgrades: Since 2015, it has been operating a whey fermentation plant, where the one million litres of whey produced each year from the production of 135 tonnes of cheese is fermented into biogas. This produces 36,000 m3 of biogas per year, equivalent to around 25,000 kWh. Additional energy is needed only in winter, to heat water and buildings. This contribution to climate protection is considerable: 5.6 tonnes of CO2 are saved each year, not least because the long transport routes previously required to dispose of the whey are no longer necessary.

Beetgold

Founded as a start-up by the Hochland Group in 2019, this Irodima subsidiary specialises in the upcycling of pomace. Pomace is the residual shell material from the pressing of fruit and vegetables that is often thrown away. Beetgold uses this raw material to make tortillas or pizza bases in place of wheat germ oil.

Stale bread into beer

Zero waste beer or ‘bread beer’, brewed partly from stale, dry bread, is also helping to combat food waste. In several regions of Germany, but also in Portugal, Finland, and Austria, producers and grocery chains are working together to produce this new beer.

Infinite Roots

This Hamburg-based food biotech startup, which now has 67 employees from 25 countries, was founded in 2018 as “Mushlabs” and is involved in mycelium research. Meat substitutes are usually made from soy, wheat, or peas. Infinite Roots uses fermented mushrooms. But not the visible fruiting bodies, but the thread-like root network – the mycelium of edible mushrooms. A particularly sustainable source of protein, as founder and CEO Mazen Rizk explains: “The mycelium is ready for harvest after only three to four days. In contrast, soybeans, which are used to make tofu, take around 140 days to harvest”.

2024 Infinite Roots has raised $58 million in a funding round for its patented technology. Among the backers, in addition to a fund from the European Innovation Council (EIC): Rewe, and the Haribo Group, which is investing heavily in future technologies such as the bio-based circular economy.

Food Rescuers

According to the Federal Environment Agency, around 11 million tonnes of food are thrown away in Germany every year, with 58 per cent of this waste stemming from private households (numbers as of 2020). Food rescuing means salvaging surplus groceries or food that is unsellable but still edible, so that instead of being disposed of, it can be redistributed to people.

Organisations such as “Foodsharing e.V.” and “Die Lebensmittelretter” (EN: “The Food Rescuers”) organise the “rescue” via internet platforms such as “Too Good To Go”, which connects users with restaurants or shops that sell surplus food at a discounted price.

‘Rescuer products’ made from rescued food or production leftovers, such as “Rettergut” chocolate or mix-chocolates, have also gained popularity. The background: ordinarily, every time the chocolate type is changed in production, hundreds of kilos of chocolate are lost as the system is “rinsed” with the purest chocolate. When production is switched from milk chocolate to dark chocolate, the first several hundred kilograms produced is so-called batch separation mass. This is a mixture of two high quality foodstuffs. As the variety of chocolate types increases, more and more type changes are required on production lines, resulting in more and more mix-chocolate. This chocolate, made from UTZ certified cocoa, is saved, processed in a CO2 neutral way, and packaged in compostable packaging.

Bureaucracy and changing perceptions – how are companies coping?

“On a meta-level, the topics of circular economy and sustainability are strongly characterised by bureaucratic requirements. On the desk of each company, so to speak, you have the EU’s Green Deal, environmental reporting, and supply chain guidelines – and they have to be dealt with,” says consumer goods distributor Gustav Ehlert, explaining his consultancy services. “But the mood is good. People are keen on doing something, they just often don’t know where to start and what exactly the framework conditions are, as they often change.”

“In the past,” explains economist Beate Gebhardt, “at each production step, value was refined and added – a linear process of food value creation. Today, everything revolves around sustainable innovations and concepts such as zero waste or plastic reduction. And all the measures required start with ‘re’: reduce, rethink, repair, reprocess, remanufacture, recycle. Everything should be done in the opposite direction to how it was done before. That is a challenge. This is where best practice examples and excellent pioneer projects can show new ways forward.”

In 2024, the independent project and research consultant Gebhardt conducted a study on sustainability excellence in agriculture and identified “hidden beacons of everyday practice” that deserve greater visibility. Gebhardt: “There are wonderful examples. Both the organic sector and conventional companies have lots of ideas about what is to be done. It's just that the organic folks are much more confident about it and better at communicating it.”

What is waste and the scandal of wastefulness?

The circular economy is anything but new in Germany. “We have a recycling law in this country that is based on the former waste disposal law, and that is no coincidence. And still today, the basic goal is to prevent things from being thrown away at the end of their life. The only question is: how do we do this, and what is waste?” What about “food losses”, such as the lettuce in the field that should not go to market for economic reasons and is therefore ploughed under? “According to the legal definition of waste, this is not waste but loss,” says Gebhardt, “it doesn't harm nature, the nutrients are returned to the cycle. But from the ethical point of view of the market, it is wastage.” Experts even call it “planned obsolescence”, as the sustainability expert knows from her studies.

Meaningful definitions of waste are essential if the circular economy is to succeed. “So my tip,” says Gebhardt, “is to make yourself a big whiteboard on obsolescence, the science of natural or premature ageing, and the shelf life of products, which comprehensively maps out the issue of throwing away and reusing food.”

The debate on food waste began when the UN organisation FAO published some alarming figures in 2011. According to these figures, 1.3 billion tonnes of food waste is generated globally each year along the entire “farm to fork” value chain. This is equivalent to almost a third of the food produced for human consumption worldwide. The amount of waste is many times greater on the production side than on the consumption side. Food waste, especially avoidable food waste, is not only an environmental and economic problem, but also an ethical one, considering the billions of starving and malnourished people in the world.

“For me, the concept of sustainability as it is embedded in the EU's Green Deal is actually a deeply economic goal,” says Gebhardt, “not primarily an environmental goal, because everything is based on market processes working in a way that takes environmental and social aspects into account. We always have to operate within this triad, even when it is a circular economy is called for.” Well, the industry is certainly heeding the call.