Reading time: 8 minutes

The meat industry is in motion: Growth, new products, and technologies, the meat substitute market with its opportunities and challenges – this industry produces a flood of news every day. The same dynamic quality is evident in the construction activities of meat companies, which are constantly building or rebuilding because they are bursting at the seams or because they are getting new machinery. These building projects are often conversions or extensions for a variety of reasons: expansion of production, new technology, increasing energy efficiency in times of high energy prices, and the need for sustainability in an energy-intensive industry.

“We have a lot of larger mid-sized companies in the meat industry,” says managing director and planning engineer Michael Trautwein in his office. With the engineering firm ATP and the consultancy FoodFab –which specialises in food companies–, Trautwein has been working for meat producers for decades. At 1,500 employees, ATP offers planning “all under one roof”, in addition to process and construction planning, “with architects, structural engineers, experts for ventilation and sanitation, refrigeration engineers – in other words, all the engineering services required for production operations,” says Trautwein, who began his career as an architect in the meat industry.

“Many producers operate on a manufacturing basis, with a very broad portfolio and in buildings that have been adapted again and again over the decades. The majority of the properties are many years old and have long since been paid off. Constructing a new building would really have to pay off –with a lot more staff and automation– to make it worthwhile. Because of the power of the market, everyone is under extreme pressure to produce cost-effectively,” says Trautwein. While the large retailers among his customers are building a lot of new facilities or outsourcing to greenfield sites, the meat industry is being forced to take a more conservative approach. There is an investment backlog in many older companies.

Modular and phased construction

Even the largest meat processors among Trautwein’s customers have long since favoured a step-by-step approach. “One customer,” recalls Trautwein, “started with a meat-cutting plant, then added a slaughterhouse, then expanded into self-service meat, then into the convenience sector.” The site was gradually expanded over a period of 30 years. “This also corresponds to our planning concept,” says Trautwein, “modular construction lets you expand a business without interrupting and restricting the existing operation.” Trautwein describes an approach that seems to be the norm in the industry.

“Conversions during ongoing operation are always exciting, because you have to take machines off the line and connect others, and approvals often take longer than you’d think,” says Tobias Metten with a satisfied smile. So far, he, his managing director Marek Huth, and the project team have weathered the permanent structural changes easily. More than 10 million cans of the traditional “Dicke Sauerländer” brand leave the Metten factory in Finnentrop, Sauerland, every year. In addition, there are over 100 products from the cooked cured products, raw and cooked sausage, and brawn segments, which are offered both as slicer items and for the service counter.

The step-by-step approach to conversions and new buildings also has a long history at this medium-sized company with 400 employees, which Tobias Metten is the fourth generation to manage: “It started in 1902 with a small butcher’s shop that grew in size over the decades, with neighbouring buildings that were bought up until we couldn’t and then we blasted a 100-metre-long rock tunnel into the mountain to salt and mature the ham on the bone,” Metten recounts from the company’s history. The company then built a new building “seven storeys high” and moved to a greenfield site in the 1980s, until the two sites were merged into a new, modern plant in the 2010s. Since then, Metten has invested a total of 17 million euros in machinery, conversions, and new facilities at the Finnentrop site, most recently five million euros into the expansion of the cooked sausage and canning department.

Efficiency and sustainability go hand in hand

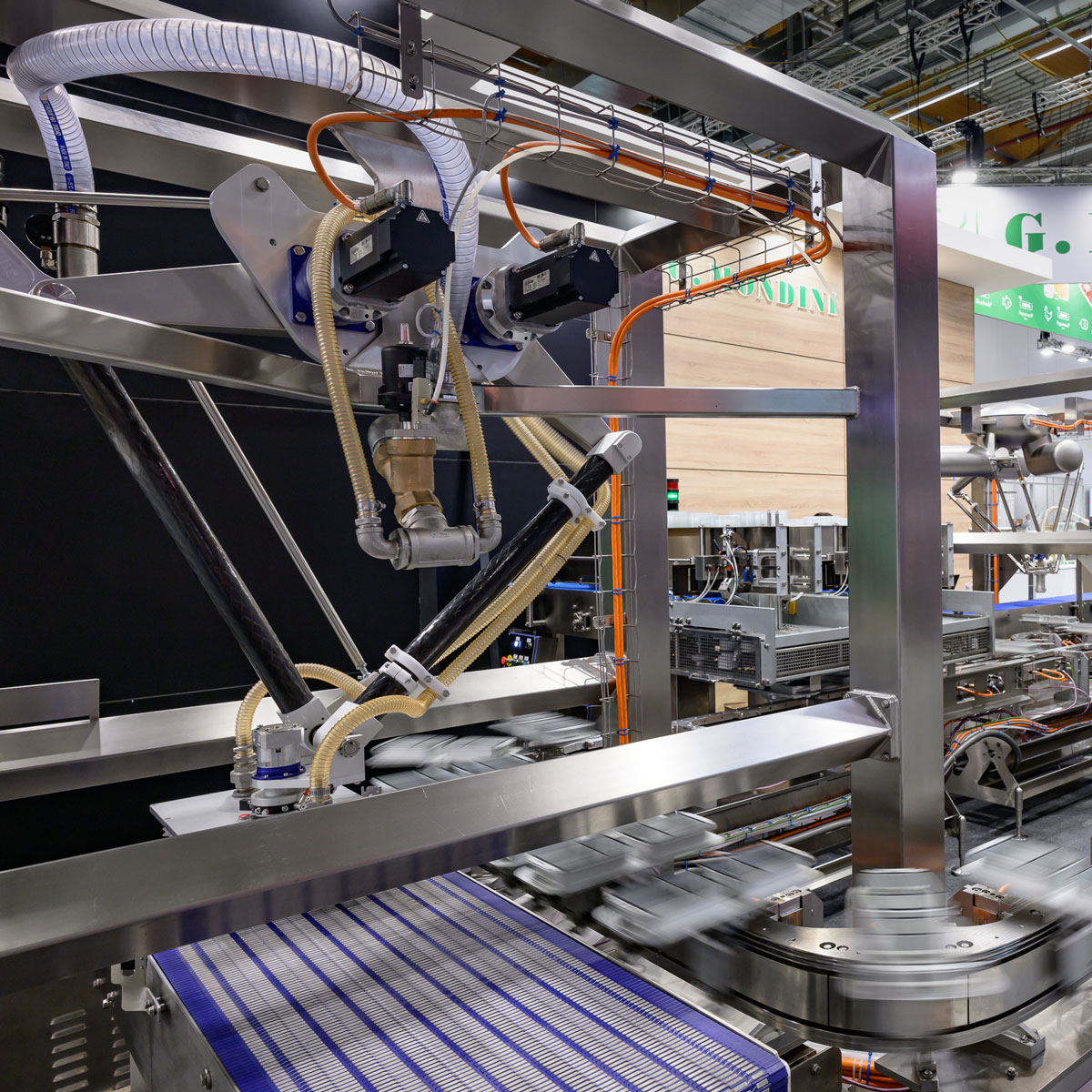

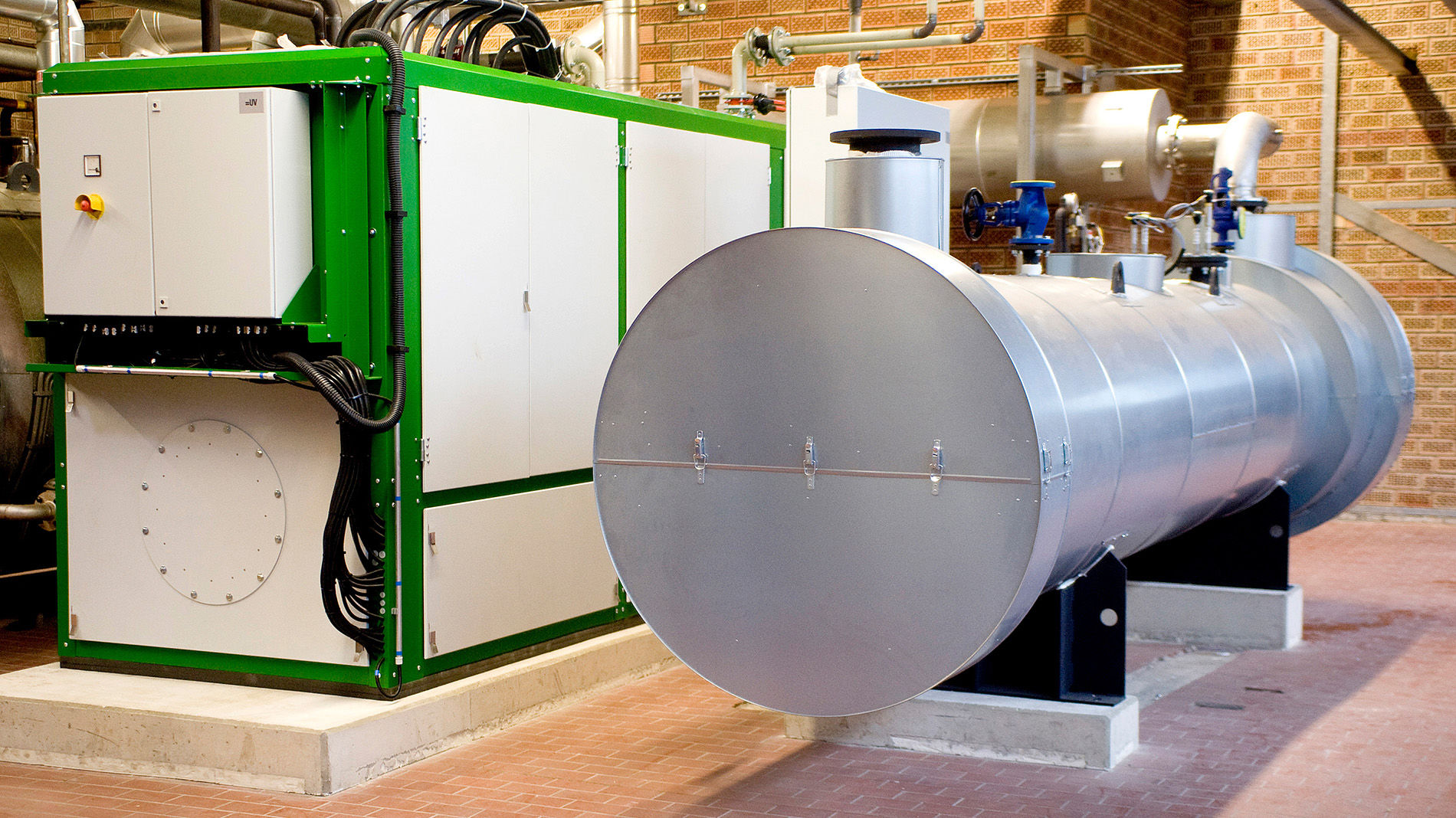

Tobias Metten believes that efficiency and sustainability must be weighed against each other with every decision, and that one cannot be made at the expense of the other: “Investments must have a long-term effect – both for the environment and for the piggy bank.” New hot water tanks, a new water treatment system, a new steam boiler, a KMA air purification system for cooking and smoking in the two additional 12-weight chambers – these were the biggest investments in the sustainability of the cooked sausage plant. A new “sausage infeed belt”, a new tray packer that automatically places the tins on trays and pallets, the expansion of the three autoclaves for sterilising the sausages to four – all this was done for efficiency, but always with sustainability in mind: “The water used to cool the autoclaves,” explains Metten, "used to be single-use in the old plant and then went down the drain. Now we work with heat recovery and a water treatment system that recirculates it.” The changes have had an impact at all levels.

“Like the triad in our logo, sustainability for us at Metten is always ecological, social, and economic. We have been fully certified according to the energy management guideline ISO 50001 for many years,” explains Metten. Under the “social” aspect, he sees employees who prefer to come to work when they know that their company is doing something for the climate. But the employees also share the responsibility: “Each individual is crucial and has to pay attention: is the water running for too long? Which seals could be leaking energy? Do the lights in the cold store need to be on all the time?”

A Green Deal for sustainable construction

Trautwein’s FoodFab offers its customers a Green Deal, which is basically an overview of all the parameters when it comes to reducing CO2 and conserving resources. According to Trautwein, “heat recovery measures are at the top of the list. 90 to 95 per cent of the energy consumed in a food production plant comes from the process itself. So everything must be done to ensure that the plant itself can recover these losses.” In Ireland, close to the sea, he has seen a company that runs entirely on wind power. “That’s not going to work for us,” says Trautwein, “but photovoltaics or biogas plants, for example in slaughterhouses – whether it’s manure or other meat by-products that we use for biogas.” The expert adds that this is called “ESG-compliant planning”, without which no financing would be possible anyway. In other words, planning that complies with the United Nations’ “Environmental, Social & Governance” regulations.

“It always depends on the location,” says Tobias Metten. “Here in the Sauerland, we are in the land of a thousand mountains. We have a lot of narrow, small valleys, and in winter the sun barely reaches the mountain peaks. That’s tricky for photovoltaics.” The alternative: “Since 2015, we have had a combined heat and power plant where we produce our electricity from gas and use the waste heat for process heat, i.e. for production. It’s very efficient.” There was a “hiccup” in the short term –due to the sudden rise in gas prices in Germany– but now that these have normalised, power-to-gas is “simply unbeatable in terms of efficiency”. Metten is therefore not giving up on photovoltaics: although the lightweight roofs of the production halls are not suitable due to the amount of snow to be expected in the mountainous Sauerland region, the social building, the dispatch cold store, the factory outlet, and open spaces are also being considered. And while the sun cannot be forced to shine higher over the mountains, “everything will get better with solar technology,” says an optimistic Tobias Metten: “The panels are getting lighter and lighter, more and more powerful, and some do not need direct sunlight at all – at some point they will be enough for us in the Sauerland valley.”

Production-related restrictions on savings

As with the water used for hygiene at Metten, Trautwein sees another industry-specific limitation to the savings potential: “We have to cool, yes. We now have temperatures of 0 to 2 °C in the pure storage rooms and 7 to 12 °C in the work rooms. But outside we now have 40 to 50°C in the summer. This is such a new issue that we have to completely change the way we work compared to 20 years ago.” The result, to prevent energy consumption for air conditioning from rising any further: insulated external panels, thicker walls. “We used to make the external panel walls of food companies 12 centimetres thick, now it’s 14 centimetres,” says Trautwein. And another aspect of the Green Deal, speaking of walls, is the reusability of the materials used. “Even solid materials such as concrete can be recycled nowadays; there is huge potential in the construction industry, where we currently have the highest waste.” Machines should also be kept in use for longer, for example by finding buyers on the international used-machinery market.

Metten describes the specific energy requirements for his production as follows: “Everything we do here is energy-intensive,” there is no use pretending, to others or to himself. “All the raw materials we process have to be heated at least once, either blanched, cooked, boiled, fried, or baked. And then cooled. Refrigeration runs 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Other products are also pasteurised or sterilised – such as for canned food. More energy is used to preserve them. So that is one side.” And what about the other, sustainable side? Metten: “Something is done to combat food waste and ensure security of supply. In addition, the cans don’t need to be refrigerated for the entire storage period, which in turn saves energy for retailers and consumers.”

Minor modifications for replacement products

The production of meat substitutes or alternative proteins is another reason in the industry for converting production facilities. A few years ago, Metten was involved in the production of hybrid products. For example, there were cooked sausage cold cuts from Herta or minced meat from large retail chains that contained roughly equal parts meat and vegetables. However, after initial tests, the product was discontinued as it was not accepted by consumers. A vegan version of the famous “Dicken Sauerländer” is still in the early stages of development; so far the results have not been convincing, especially in terms of “bite” – and developing meat substitutes for the sterilised can is a challenge in itself, according to Metten. The traditional company therefore sees itself in the future as a “craftsman’s business with a focus on high-quality sausage specialities”. Tobias Metten sees the contribution of medium-sized companies to sustainability in dimensions such as regionality, brand, customer relations, service, and craftsmanship, rather than in the research-intensive, high-tech production of what are ultimately synthetic foods.

Nevertheless, Metten is involved in a project run by the University of Giessen and RWTH Aachen, a small research institute in Siegen and the Nordzucker Group. The aim is to combine residual streams from sugar beet production and sugar beet pulp with fungi in a fermenter in order to cultivate a new protein. This would make it possible to dispense with vegetables and soy as the basis for meat substitutes. So far, says Metten, the protein produced in this way has always been too liquid to be used in sausage production. Optimising this is one of several challenges in the research project.

97 per cent of Germans buy sausage

Once the sausage-mixture has been produced, the process of production is very similar for meat or alternative products: “That might mean you want to convert facilities, or not,” says Michael Trautwein. Tobias Metten takes a similar view: “The fact that vegetarian or hybrid products can be produced on the same machines is definitely an advantage for the industry. They can be realised with systems from well-known machine manufacturers." Theoretically, the form of the substitute product would then not be pre-defined but would primarily be informed by production requirements – and, as with traditional sausages with all of their cultural significance, can also be the marketing argument. You might even call this a win-win situation.

Metten cites a YouGov survey which shows that 97 per cent of Germans buy sausages at least once a year. This so-called consumer reach is still very high, which is also reflected in the size of the total sausage market of 1.3 million tonnes per year. Given the small market share of alternative products, any reduction in resources in the conventional sector, however small, has more climate impact than any innovation of even the most successful substitute product. And here comes FoodFab boss Trautmann with an example: “Let’s take water consumption in the pig slaughterhouse alone. The current guidelines say 300 litres per pig. But if I were to build a plant today where one pig consumes 300 litres of water, the client would declare me totally incompetent.” Pause. “Because today we are already using less than 200 litres in some cases.” With around 45 million pigs slaughtered every year in Germany alone, this difference is equivalent to the water supply of an entire medium-sized city.